Examples of Projects in History

One way to gain perspective on projects of today is to compare them with

projects of the past. In some ways, projects remain the same as they have

always been, and in some ways, project management has evolved over the

ages. Let us review a few projects from history where enough evidence has

been gained through research and historical records to make some project

management comparisons.

Project: Building the Egyptian Great Pyramid at Giza

One of the first major undertakings that project managers clearly identify

as a project is the construction of the great pyramid at Giza. There is some

historical evidence—we could call it project history—that gives us insight

into its scope and effort.

Project records exist in the writings of Greek philosophers, Egyptian

hieroglyphics, and archeological findings. High-level estimates of time and

effort “in the press” during that period were apparently inaccurate.

Herodotus wrote that the pyramid took 100,000 people 30 years to complete.

Archeological research and records pare those estimates to 20,000

people and 20 years to complete. Hieroglyphics in the tombs reveal some

of the methods (technical approaches and tools) used to construct the pyramid:

Stone blocks were carved from a quarry by hand using stone hammers

and chisels. Then the stones were slid on pallets of wood over wet sand, and

workers used wooden beams as levers to heft them into the desired position.

The team, according to research, was not 100,000 people, as originally

recorded by Herodotus; that would have been approximately 10 percent

of the entire population of Egypt—and more than 3 million effort-years. It

was more likely 20,000 people, 2,000 of whom were continuous in their

service (the core team) and 18,000 of whom were tracked by DNA evidence

in bones on the site to villages all over Egypt. If we were to translate their

structure into a modern context, this would correspond to a core team (the

ancient group of continuous service) with various team members temporarily

assigned as resources from the departments (the ancient villages)

in the sponsor’s organization (the ancient dynasty). The work shift was long

in those days; the team rotation was about 12 weeks. At that point the workers

on loan to the project went home and were replaced by new workers.

The power of the project sponsor was very helpful in getting such a

huge project done. The project sponsor was executive management (the

pharaoh also was viewed as “god”—making it easier to get permission to

leave the family and village job to work on the assignment). The work was hard, there were occupational hazards (bone damage), and the pay was low

(including fresh onions for lunch). People who died on the project were

buried on the project site (hence the DNA evidence to trace their villages).3

Saturday, June 15, 2013

Project Management’s Underlying Assumptions

Project Management’s Underlying Assumptions

There are a few fundamental concepts that, once accepted, make many of

the unique practices and processes in project management more logical.

■ Risk. Organizations need to believe the risks inherent in a project to

provide adequate management backing and support, and the team

needs accurate and timely risk information. When doing something

new for the first time, there are many unknowns that have a potential

to affect the project in some way, positive or negative. One goal

is to “flush out” as many of those unknowns as possible—like a

bird dog flushes birds out of the bushes—so that they may be managed,

and the project’s energy can be redirected to managing the

surprises that inevitably arise when the work is unfamiliar.

■ Authority. Because the project has a start and an end and specified

resources, there is a need to balance the competing requirements of

time, cost, and performance. The authority to balance these competing

requirements is delegated to the project manager and the

team.

■ Autonomy. The risks associated with the project must be managed

so that they do not obstruct progress. As risks mature into real

issues or problems, the project manager and team need autonomy

and flexibility to resolve some and ignore others based on their

potential to hurt the project.

■ Project control. To anticipate and predict needed change, the project

manager and team need ways to determine where they are in

relation to the projected time, cost, and performance goals. They

use this status information to make needed adjustments to the plan

and to refine its execution strategy.

■ Sponsorship. The project manager and team need the backing of

management, or a sponsor and champion, to ensure that the project is aligned properly with executive goals, to protect against external

interference, and to provide resource backing

There are a few fundamental concepts that, once accepted, make many of

the unique practices and processes in project management more logical.

■ Risk. Organizations need to believe the risks inherent in a project to

provide adequate management backing and support, and the team

needs accurate and timely risk information. When doing something

new for the first time, there are many unknowns that have a potential

to affect the project in some way, positive or negative. One goal

is to “flush out” as many of those unknowns as possible—like a

bird dog flushes birds out of the bushes—so that they may be managed,

and the project’s energy can be redirected to managing the

surprises that inevitably arise when the work is unfamiliar.

■ Authority. Because the project has a start and an end and specified

resources, there is a need to balance the competing requirements of

time, cost, and performance. The authority to balance these competing

requirements is delegated to the project manager and the

team.

■ Autonomy. The risks associated with the project must be managed

so that they do not obstruct progress. As risks mature into real

issues or problems, the project manager and team need autonomy

and flexibility to resolve some and ignore others based on their

potential to hurt the project.

■ Project control. To anticipate and predict needed change, the project

manager and team need ways to determine where they are in

relation to the projected time, cost, and performance goals. They

use this status information to make needed adjustments to the plan

and to refine its execution strategy.

■ Sponsorship. The project manager and team need the backing of

management, or a sponsor and champion, to ensure that the project is aligned properly with executive goals, to protect against external

interference, and to provide resource backing

General Rules for Project Management

General Rules for Project Management

In sports, whether one is participating or simply watching the game, one

needs to understand not just the sport itself but also the rules associated

with it. There are different rules and roles in team sports such as football or

soccer, and cricket. Automobile racing has different rules and roles from

horse racing and ski racing. Applying experience and knowledge associated

with one sport while watching a different sport would lead to frustration,

discouragement, and eventually rejection. Similarly, applying rules that

apply to routine business operations in a project context would lead to similar

frustration, discouragement, and rejection. As obvious as this concept

seems, the application of operations management concepts to projects

occurs regularly on a daily basis. In many organizations, both the project

team and the sponsoring management share this negative experience but do

not realize why it is occurring.

What makes a project temporary and unique also makes it unsuited to

the rules and roles of operations management.

Roles in project management are different from those in operations.

In operations, a manager in finance will have a different job from a manager

in human resources or product development, but a project manager

will have a very similar job whether the project is a finance project, a

human resources project, or a product development project. While a line

manager can push a problem “upstairs” to a higher level manager, or evendelay its resolution, the project manager is expected to manage the risks,

problems, and resolutions within the project itself, with the help of the

team, the sponsor or the customer, to keep the project moving forward.

Project manager is a clearly a role; the project manager is the person

responsible for the management and results of the project. Some organizations

with established project management functions (such as a project

management office) will have a job description and position classification

for project manager, and some even deploy project managers to other divisions

when that expertise and role are needed. But the position is not just a

manager role with a different title on it. The performance expectations are

as different from each other as offensive or defensive positions on a sports

team. Project management roles are always “offensive”

In sports, whether one is participating or simply watching the game, one

needs to understand not just the sport itself but also the rules associated

with it. There are different rules and roles in team sports such as football or

soccer, and cricket. Automobile racing has different rules and roles from

horse racing and ski racing. Applying experience and knowledge associated

with one sport while watching a different sport would lead to frustration,

discouragement, and eventually rejection. Similarly, applying rules that

apply to routine business operations in a project context would lead to similar

frustration, discouragement, and rejection. As obvious as this concept

seems, the application of operations management concepts to projects

occurs regularly on a daily basis. In many organizations, both the project

team and the sponsoring management share this negative experience but do

not realize why it is occurring.

What makes a project temporary and unique also makes it unsuited to

the rules and roles of operations management.

Roles in project management are different from those in operations.

In operations, a manager in finance will have a different job from a manager

in human resources or product development, but a project manager

will have a very similar job whether the project is a finance project, a

human resources project, or a product development project. While a line

manager can push a problem “upstairs” to a higher level manager, or evendelay its resolution, the project manager is expected to manage the risks,

problems, and resolutions within the project itself, with the help of the

team, the sponsor or the customer, to keep the project moving forward.

Project manager is a clearly a role; the project manager is the person

responsible for the management and results of the project. Some organizations

with established project management functions (such as a project

management office) will have a job description and position classification

for project manager, and some even deploy project managers to other divisions

when that expertise and role are needed. But the position is not just a

manager role with a different title on it. The performance expectations are

as different from each other as offensive or defensive positions on a sports

team. Project management roles are always “offensive”

PROJECT MANAGEMENT CONCEPTS

PROJECT MANAGEMENT

CONCEPTS

OVERVIEW AND GOALS

This chapter provides a general overview of the role projects have played in

the world and how projects in history, as well as projects today, share fundamental

elements. It defines the project life cycle, the product life cycle,

and the process of project design that integrates and aligns the two into one

or more projects.

The triple constraint is introduced as important in defining and managing

projects. How project management evolved helps to explain how it is

applied in different settings today, and why those differences developed.

And while the standard life cycle for projects applies “as is” uniformly

across industries, it requires developing different levels and types of detail

on projects. Tailoring general project management approaches is proposed

based on the types of projects being managed.

WHAT IS A PROJECT?

In Chapter 1 we distinguished projects, which are temporary and unique,

from operations, which are ongoing and repetitive.1 Projects have little, if

any, precedent for what they are creating, the project work is new, and work-

ers are unfamiliar with expectations. On the other hand, operations are

repetitive, routine business activities. They are familiar and documented.

They have benefited by improvements over time, and worker expectations

are written into job descriptions.

Thousands of project management professionals have agreed that a

project has a clear beginning and a clear end, as well as a resulting product

or service that is different in some significant way from those created

before. The unique product or service in a project management setting is

often called a deliverable, a generic term that allows discussion about the

result without getting specific about its characteristics. The project’s deliverable

may be the ultimate product or service, or it may be a clearer definition

needed for the next consecutive project, such as a design or a plan. In

some cases it may be just one part of the final deliverable, consisting of outputs

of multiple projects.2

The reason the distinction is important that projects have “a clear

beginning, a clear end, and a unique product or service” is that the “rules”

for managing projects are different than the “rules” for managing operations.

The roles of the people in relation to the project are different as well.

To better understand the distinction, we can compare it with how the rules

and roles differ in sports.

CONCEPTS

OVERVIEW AND GOALS

This chapter provides a general overview of the role projects have played in

the world and how projects in history, as well as projects today, share fundamental

elements. It defines the project life cycle, the product life cycle,

and the process of project design that integrates and aligns the two into one

or more projects.

The triple constraint is introduced as important in defining and managing

projects. How project management evolved helps to explain how it is

applied in different settings today, and why those differences developed.

And while the standard life cycle for projects applies “as is” uniformly

across industries, it requires developing different levels and types of detail

on projects. Tailoring general project management approaches is proposed

based on the types of projects being managed.

WHAT IS A PROJECT?

In Chapter 1 we distinguished projects, which are temporary and unique,

from operations, which are ongoing and repetitive.1 Projects have little, if

any, precedent for what they are creating, the project work is new, and work-

ers are unfamiliar with expectations. On the other hand, operations are

repetitive, routine business activities. They are familiar and documented.

They have benefited by improvements over time, and worker expectations

are written into job descriptions.

Thousands of project management professionals have agreed that a

project has a clear beginning and a clear end, as well as a resulting product

or service that is different in some significant way from those created

before. The unique product or service in a project management setting is

often called a deliverable, a generic term that allows discussion about the

result without getting specific about its characteristics. The project’s deliverable

may be the ultimate product or service, or it may be a clearer definition

needed for the next consecutive project, such as a design or a plan. In

some cases it may be just one part of the final deliverable, consisting of outputs

of multiple projects.2

The reason the distinction is important that projects have “a clear

beginning, a clear end, and a unique product or service” is that the “rules”

for managing projects are different than the “rules” for managing operations.

The roles of the people in relation to the project are different as well.

To better understand the distinction, we can compare it with how the rules

and roles differ in sports.

BENEFITS OF ADOPTING PROJECT MANAGEMENT APPROACHES

BENEFITS OF ADOPTING PROJECT

MANAGEMENT APPROACHES

Recent research and publications help in quantifying the benefits of project

management, including executive surveys of what they consider to be its

benefits.22 However, continuous improvement should be the norm; good

performance “on average” is not sufficient (see Figure 1-6).

The negative impact of not practicing effective methods of project

management includes the escalating costs of high-profile projects. The risk

is that the sponsoring organization does not achieve its desired goals despite

its investment in the project. Some analysts have suggested that a company’s

stock price can drop if a failed project becomes public news.23

Taking a systematic approach to managing projects creates a number

of benefits, regardless of the host organization’s particular emphasis on outcomes.

These benefits are:

■ Quicker completion. Quicker time-to-market delivery of rapid

development can make all the difference in the profitability of a

commercial product. It is said that one-third of the market goes to

the first entrant when a breakthrough product is introduced. In

some sectors, delays enact penalties.

■ More effective execution. When projects are formed to create a

desired product first, the project that delivers results on schedule

simultaneously may deliver large profits to the host company.

Other projects must meet exact requirements.

■ More reliable cost and schedule estimates. Making adequate

resources available when they are needed increases the likelihood

that a project will deliver benefits or services within budget and

resource constraints. Resources can be leveraged.

■ Reduced risk. For highly visible projects, such as shuttle launches

and space exploration, the potential loss of life is an unacceptable

political downside to a project that does not deliver. In not-for-profit

organizations, the losses associated with a failed project may

consume the resource contingencies of the whole organization or

make its reputation unacceptable to its member customers. The

organization’s actual existence—continuation of a whole organization—

can be at risk if losses exceed the organization’s capital

reserve.

■ Reduced cost. Maximizing schedules, linking dependent tasks, and

leveraging resources ultimately reduce waste, including wasted

time and effort on the part of the project team’s highly skilled and

trained staff.

A major benefit of adopting project management is that it raises

awareness of costs, complexities, risks, and benefits early in the process of

development, enabling sponsors to know where they stand in proceeding

with a given commitment and allowing action to reduce negative influences

so that the investment pays dividends and delivers on its promises.

The end result is that society gets benefits with the expenditure of fewer

resources.

What is ultimately needed is an environment where systems and

processes work together with knowledgeable and skilled professionals to

deliver on the promises of project management. While mature integration

has not yet been achieved, this new direction is well on its way.

MANAGEMENT APPROACHES

Recent research and publications help in quantifying the benefits of project

management, including executive surveys of what they consider to be its

benefits.22 However, continuous improvement should be the norm; good

performance “on average” is not sufficient (see Figure 1-6).

The negative impact of not practicing effective methods of project

management includes the escalating costs of high-profile projects. The risk

is that the sponsoring organization does not achieve its desired goals despite

its investment in the project. Some analysts have suggested that a company’s

stock price can drop if a failed project becomes public news.23

Taking a systematic approach to managing projects creates a number

of benefits, regardless of the host organization’s particular emphasis on outcomes.

These benefits are:

■ Quicker completion. Quicker time-to-market delivery of rapid

development can make all the difference in the profitability of a

commercial product. It is said that one-third of the market goes to

the first entrant when a breakthrough product is introduced. In

some sectors, delays enact penalties.

■ More effective execution. When projects are formed to create a

desired product first, the project that delivers results on schedule

simultaneously may deliver large profits to the host company.

Other projects must meet exact requirements.

■ More reliable cost and schedule estimates. Making adequate

resources available when they are needed increases the likelihood

that a project will deliver benefits or services within budget and

resource constraints. Resources can be leveraged.

■ Reduced risk. For highly visible projects, such as shuttle launches

and space exploration, the potential loss of life is an unacceptable

political downside to a project that does not deliver. In not-for-profit

organizations, the losses associated with a failed project may

consume the resource contingencies of the whole organization or

make its reputation unacceptable to its member customers. The

organization’s actual existence—continuation of a whole organization—

can be at risk if losses exceed the organization’s capital

reserve.

■ Reduced cost. Maximizing schedules, linking dependent tasks, and

leveraging resources ultimately reduce waste, including wasted

time and effort on the part of the project team’s highly skilled and

trained staff.

A major benefit of adopting project management is that it raises

awareness of costs, complexities, risks, and benefits early in the process of

development, enabling sponsors to know where they stand in proceeding

with a given commitment and allowing action to reduce negative influences

so that the investment pays dividends and delivers on its promises.

The end result is that society gets benefits with the expenditure of fewer

resources.

What is ultimately needed is an environment where systems and

processes work together with knowledgeable and skilled professionals to

deliver on the promises of project management. While mature integration

has not yet been achieved, this new direction is well on its way.

THE VALUE-ADDED PROPOSITION: DECLARING AND REVALIDATING PROJECT VALUE

THE VALUE-ADDED PROPOSITION:

DECLARING AND REVALIDATING

PROJECT VALUE

Usually the selection of a project for funding and authorization includes a

careful analysis of the value it is to provide its intended audiences.

However, changes occur in the environment, regulations, social interests,

and market opportunities while a project is under way. Sometimes the outcome

of another project, or even reorganization, can make the outcome of

a current project obsolete. It is important not only to communicate the value

of a project at its inception but also to revalidate the effort and expenditure

at key intervals, especially for lengthy projects.

It would be ideal if a project’s value could be established in practical

terms so that the project’s management, sponsor, customers, and users

could agree that it had delivered on its promises. Some of the ways to gain

agreement on objective measures are addressed in Chapters 6 and 12. Those

familiar with the benefits of project management do not need “objective”

reasons; they feel that the reduced ambiguity, managed risk, shortened time

frames, and product existence are benefits enough.

William Ibbs and Justin Reginato, in their research study entitled

Quantifying the Value of Project Management,20 cited a number of dimensions

where organizations reaped tangible benefits. But some sectors discount

project management’s contributions or diminish its overall scope.

Most of these are low on the scale of organizational project management

maturity because the higher the maturity level, the greater are the realized

benefits. Companies with more mature project management practices have

better project performance.21

Spending a little time defining the different benefits of project management

according to the primary values of its own economic sector will

help an organization to clarify how value can be delivered by a project in

its own context. Some sectors will benefit from a focus on resource leverage

or efficiency; others, from a focus on maturity. After such an analysis

is complete, the strategic objectives of the organization and its

management, customers, and user groups need to be considered. Success

criteria built into the plan ensures that all know what the goals of the project

entail.

DECLARING AND REVALIDATING

PROJECT VALUE

Usually the selection of a project for funding and authorization includes a

careful analysis of the value it is to provide its intended audiences.

However, changes occur in the environment, regulations, social interests,

and market opportunities while a project is under way. Sometimes the outcome

of another project, or even reorganization, can make the outcome of

a current project obsolete. It is important not only to communicate the value

of a project at its inception but also to revalidate the effort and expenditure

at key intervals, especially for lengthy projects.

It would be ideal if a project’s value could be established in practical

terms so that the project’s management, sponsor, customers, and users

could agree that it had delivered on its promises. Some of the ways to gain

agreement on objective measures are addressed in Chapters 6 and 12. Those

familiar with the benefits of project management do not need “objective”

reasons; they feel that the reduced ambiguity, managed risk, shortened time

frames, and product existence are benefits enough.

William Ibbs and Justin Reginato, in their research study entitled

Quantifying the Value of Project Management,20 cited a number of dimensions

where organizations reaped tangible benefits. But some sectors discount

project management’s contributions or diminish its overall scope.

Most of these are low on the scale of organizational project management

maturity because the higher the maturity level, the greater are the realized

benefits. Companies with more mature project management practices have

better project performance.21

Spending a little time defining the different benefits of project management

according to the primary values of its own economic sector will

help an organization to clarify how value can be delivered by a project in

its own context. Some sectors will benefit from a focus on resource leverage

or efficiency; others, from a focus on maturity. After such an analysis

is complete, the strategic objectives of the organization and its

management, customers, and user groups need to be considered. Success

criteria built into the plan ensures that all know what the goals of the project

entail.

How Different Organizations Define the Value of Projects

How Different Organizations Define the Value of Projects

The value produced by the practice of project management is not the

same in every sector of the economy (see Figure 1-5). With the risk of oversimplifying,

■ Corporate projects need to make money, and projects are judged by

their contribution to increasing revenue or cutting unnecessary

cost.

■ Not-for-profit organizations are charged with providing benefits to

a broader society, and projects considered successful have broad or

conspicuous contributions.

■ Government projects must provide needed services or benefits to

groups defined by law. Projects that provide those services or benefits

to the stakeholders of public programs and services, and do so

within the regulations, are considered successful.

The value produced by the practice of project management is not the

same in every sector of the economy (see Figure 1-5). With the risk of oversimplifying,

■ Corporate projects need to make money, and projects are judged by

their contribution to increasing revenue or cutting unnecessary

cost.

■ Not-for-profit organizations are charged with providing benefits to

a broader society, and projects considered successful have broad or

conspicuous contributions.

■ Government projects must provide needed services or benefits to

groups defined by law. Projects that provide those services or benefits

to the stakeholders of public programs and services, and do so

within the regulations, are considered successful.

FIGURE 1-5 Benefits of adopting project management approaches. Different sectors derive significant value from project management by achieving strategic goals.

■ Academia organizes knowledge into curricula and courses of study, and projects that push knowledge into new areas or advance human understanding are recognized as valuable. Project management must be sufficiently challenging intellectually to warrant attention from leading scholarly institutions

Long-Term Value of Project Outcomes

Long-Term Value of Project Outcomes

Major undertakings produce outcomes that are believed to deliver great value to their users. It is difficult to know whether a major project will be short-lived or will endure over time. As necessary as they may be when begun, some projects deliver important results for only a short period of time and then are replaced by new methods or new technology. Others persist.

The Panama Canal connected two great oceans, and the reversal of the Chicago River—an engineering marvel—linked the East Coast shipping trade with the great Mississippi transportation corridor. But railroads swift-ly replaced shipping as a low-cost method of moving people and goods over long distances. The railroad projects across the northern states adopted a standard gauge and could be connected into a vast transportation network. But the southern states adopted a narrower gauge and had to reset their tracks to benefit from this vast network.

There are intangible benefits to project outcomes as well. The Eiffel Tower in Paris and the Space Needle in Seattle—both engineered to draw attention to a big event—put those cities on the map for tourism and marked them with emblems of innovation that have endured. The astro-nomical wonder of Stonehenge in England, huge stone statues in Africa and Asia, South America’s “lost cities” in the Andes, and the cathedrals of Europe inspired the people of the past, and they continue to inspire us today (see Figure 1-4).

Viewing the results of massive projects in history reminds us that our advanced technology, learning, and project methods have shortened the timeframes needed to get project results. Cathedrals sometimes took 200 years to complete; the World Trade Center was built in 20 years. But a still longer view is needed. Sometime in the next five years the United States will have to address the upgrade of its vast network of interstate highways, which were built after World War II. But five years is not an adequate length of time for such a large undertaking. Many of the government planning agencies were found in the late 1980s to have no plan for raising funds to maintain society’s infrastructure.17

Major undertakings produce outcomes that are believed to deliver great value to their users. It is difficult to know whether a major project will be short-lived or will endure over time. As necessary as they may be when begun, some projects deliver important results for only a short period of time and then are replaced by new methods or new technology. Others persist.

The Panama Canal connected two great oceans, and the reversal of the Chicago River—an engineering marvel—linked the East Coast shipping trade with the great Mississippi transportation corridor. But railroads swift-ly replaced shipping as a low-cost method of moving people and goods over long distances. The railroad projects across the northern states adopted a standard gauge and could be connected into a vast transportation network. But the southern states adopted a narrower gauge and had to reset their tracks to benefit from this vast network.

There are intangible benefits to project outcomes as well. The Eiffel Tower in Paris and the Space Needle in Seattle—both engineered to draw attention to a big event—put those cities on the map for tourism and marked them with emblems of innovation that have endured. The astro-nomical wonder of Stonehenge in England, huge stone statues in Africa and Asia, South America’s “lost cities” in the Andes, and the cathedrals of Europe inspired the people of the past, and they continue to inspire us today (see Figure 1-4).

Viewing the results of massive projects in history reminds us that our advanced technology, learning, and project methods have shortened the timeframes needed to get project results. Cathedrals sometimes took 200 years to complete; the World Trade Center was built in 20 years. But a still longer view is needed. Sometime in the next five years the United States will have to address the upgrade of its vast network of interstate highways, which were built after World War II. But five years is not an adequate length of time for such a large undertaking. Many of the government planning agencies were found in the late 1980s to have no plan for raising funds to maintain society’s infrastructure.17

Not only our individual enterprises but also our society as a whole needs to have the infrastructure in place to initiate, fund, plan, and execute major projects. Currently, many separate agencies are responsible for dif-ferent parts of these massive projects. Running nationwide projects without a central project authority in government is much like running projects sep-arately within a large organization. A realistic supportive environment is important if we want to ensure project success and keep costs down. Where is this project management initiative to come from?

In Capetown, South Africa, a large segment of freeway stands above town along the waterfront, built by government officials without consider-ation for the funding required to link it with other transportation systems. Local project managers say that the city leaves it there as a reminder to think long range in their planning.18

Professional ethics address the professional project manager’s respon-sibility to society and the future. While it is easy to say that a project is only responsible for the outcome defined for that project over the period of time it is in existence, we know that the outcomes have a life cycle, and quality and value are assessed over the entire life cycle of a product or service until it is eliminated, demolished, or removed from service. Considering how it will endure over time or be maintained is part of management’s responsi-bility, but the project manager has the opportunity to build such considera-tions into the plan.

Cooperation Builds the Future

Fortunately, professional societies in the field of project management have begun working with government agencies in a number of different countries to integrate project management with the school systems and the policies governing public projects. More on these topics will be addressed in later chapters.19 In Chapter 12 we address how mature project environments manage the interdependent elements of projects.

Failed Projects Spur Improvement

Thanks to modern communications technology, failed projects also have staked out a space in human history. We may not consider them projects or even know why they failed, but they sit as examples in our minds as we con-template a new undertaking. We see images of ancient cities in the Middle East covered by desert sands, victims of environmental degradation. The steamship Titanic rests on the ocean floor, an engineering marvel that fell prey to its own self-confidence. Other less visible project failures are in our conscious minds through the news media. The Alaskan oil spill, the release of nuclear pollution onto the Russian plain, attempts to stem the AIDS epi-demic’s relentless march—all are common project examples in our news media and our history books. All share the legacy and challenges of project management. Ambitious projects continue to be conceived, planned, executed, and completed—with varying degrees of “success.” Sometimes teams study these examples to capture learning and improve our project track record in the future. Sometimes we have no answers, just the reminder of risk unmanaged or faulty assumptions.

Projects typically are carried out in a defined context by a specific group of people. They are undertaken to achieve a specific purpose for inno-vators, sponsors, and users. But project delivery of something new is also judged in a broader context of value. Projects are not judged at a single point in time but over the life cycle of the project’s product or outcome. Managing complex project interdependencies as well as the future effects of the proj-ect is part of the professional challenge. It is the profession of project man-agement that is devoted to increasing the value and success of projects and ensuring that what is delivered meets expectations of not just immediate users but of a broader set of stakeholders. This broader definition of project success is another element driving project management toward a profession.

Comparing Project Management with Problem Solving

Comparing Project Management with Problem Solving

The phases of a project are basically the same as an individual’s method of problem solving, but when the project’s outcome is bigger or more chal-lenging, the system breaks down. People in separate functional departments see the problem differently. Agreed-on approaches get interpreted differ-ently by specialists with diverse values and training. Actions influence other actions, sometimes undercutting each other or slowing implementation. Somehow, small problems can evolve into a myriad of complexities, dependencies, and challenges. Priorities become difficult to sort out.

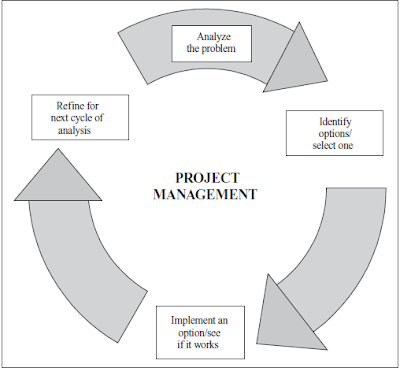

Projects require a process just like in problem solving (see Figure 1-3). The first phase, usually called initiation, is when the idea is worked out and described, its scope and success criteria defined, its sponsors identified, its resources estimated, and its authority formalized. Then the project manager and team decide how it can be achieved practically, plan it out, and allocate the resources and risks by task and phase. Finally, the project manager and team put the plan into action during project execution. Project management professionals counter the complexity just described by formalizing the process. They then orchestrate it with teams, managing task interfaces, reducing risk, and solving the remaining implementation problems within resource and time constraints. Once they have the experience behind them, they assess whether it turned out the way it was expected to, why or why not, and define what can be done better next time. The group applies the learn-ing to sequential projects and makes best-practice examples available to

FIGURE 1-3 Comparing project management with problem solving. Both proj-ect management and problem solving require a process to be effective.

The phases of a project are basically the same as an individual’s method of problem solving, but when the project’s outcome is bigger or more chal-lenging, the system breaks down. People in separate functional departments see the problem differently. Agreed-on approaches get interpreted differ-ently by specialists with diverse values and training. Actions influence other actions, sometimes undercutting each other or slowing implementation. Somehow, small problems can evolve into a myriad of complexities, dependencies, and challenges. Priorities become difficult to sort out.

Projects require a process just like in problem solving (see Figure 1-3). The first phase, usually called initiation, is when the idea is worked out and described, its scope and success criteria defined, its sponsors identified, its resources estimated, and its authority formalized. Then the project manager and team decide how it can be achieved practically, plan it out, and allocate the resources and risks by task and phase. Finally, the project manager and team put the plan into action during project execution. Project management professionals counter the complexity just described by formalizing the process. They then orchestrate it with teams, managing task interfaces, reducing risk, and solving the remaining implementation problems within resource and time constraints. Once they have the experience behind them, they assess whether it turned out the way it was expected to, why or why not, and define what can be done better next time. The group applies the learn-ing to sequential projects and makes best-practice examples available to

FIGURE 1-3 Comparing project management with problem solving. Both proj-ect management and problem solving require a process to be effective.

other projects in the organization. The phases of a project closely resemble

the stages of problem solving: initiation/concept development (analyze the

problem), high-level/detailed planning (identify options/select one), execution/

control (implement an option/see if it works), and closure and lessons

learned (refine for next cycle of analysis).

Benefits of Managing Organizational Initiatives Systematically

Benefits of Managing Organizational Initiatives Systematically

Why do organizations need project management? When initiatives with

high risk and change are undertaken, a systematic process for managing

known unknowns frees time, energy, and resources for managing unknown

unknowns. This sort of “risk triage” increases the chances that the project

will deliver successfully on its commitments using the committed

resources. There are a lot of elements to manage. Figure 1-2 shows some of

the benefits to managing them more systematically using project management

disciplines and practices.

■ Visibility into the problem. The analysis that goes into systematic

management reveals a lot of hidden issues, overlaps, and trends that

were not visible before. If management is to resolve organizational

challenges, it must first make them visible. A precept of project

management is to make the invisible visible so that it can be managed.

16 Management consultants consider the biggest challenges in

working with organizations not to be the identified problems but

rather to be the unspoken ones.

■ Leveraging scarce resources. The money, time, and effort to undertake

organizational initiatives are finite. To get the most leverage

out of them, resources should be made available only when they are

needed, and they should be transferred to more pressing needs

when a particular initiative is over. Unless management knows

what exists and its status in terms of completion, scarce resources

can be scattered and not used effectively.

■ Building a skills base. Most of the key functions present in organizations

are also present in projects, but they are abbreviated, condensed,

or applied in unique ways. For individuals in project

management, learning the fundamentals of most organizational

functions, as well as those unique to project management, comprises

the basics. Mastery takes commitment and dedication over a

number of years. As staff members learn project management, they

also learn the fundamentals of organization functions so that they

make more informed decisions in their work for the organization.

■ Planning for easy changes in the future. Managing organizational

initiatives systematically preserves the overall quality of the outcomes

for stakeholders and the organization as a whole.

As an analogy, consider a person building a house with only a general

plan and no architectural drawings. By means of routine decisions, myriad

minor compromises occur without any overall intent to compromise:

The number and placement of electrical outlets can affect the use of appliances

and limit future work capacity; unplanned placement of vents and

piping can affect future comfort and ability to manage temperature; and

placement of load-bearing walls can affect remodeling or later modification.

Use of different standards for different parts of the construction can

prevent later consolidation of separate systems.Seemingly minor compromises can erode the overall quality of life for

the occupants and limit what can be done with the house in the future.

Many such ad hoc houses are in fact demolished and replaced because it is

Why do organizations need project management? When initiatives with

high risk and change are undertaken, a systematic process for managing

known unknowns frees time, energy, and resources for managing unknown

unknowns. This sort of “risk triage” increases the chances that the project

will deliver successfully on its commitments using the committed

resources. There are a lot of elements to manage. Figure 1-2 shows some of

the benefits to managing them more systematically using project management

disciplines and practices.

■ Visibility into the problem. The analysis that goes into systematic

management reveals a lot of hidden issues, overlaps, and trends that

were not visible before. If management is to resolve organizational

challenges, it must first make them visible. A precept of project

management is to make the invisible visible so that it can be managed.

16 Management consultants consider the biggest challenges in

working with organizations not to be the identified problems but

rather to be the unspoken ones.

■ Leveraging scarce resources. The money, time, and effort to undertake

organizational initiatives are finite. To get the most leverage

out of them, resources should be made available only when they are

needed, and they should be transferred to more pressing needs

when a particular initiative is over. Unless management knows

what exists and its status in terms of completion, scarce resources

can be scattered and not used effectively.

■ Building a skills base. Most of the key functions present in organizations

are also present in projects, but they are abbreviated, condensed,

or applied in unique ways. For individuals in project

management, learning the fundamentals of most organizational

functions, as well as those unique to project management, comprises

the basics. Mastery takes commitment and dedication over a

number of years. As staff members learn project management, they

also learn the fundamentals of organization functions so that they

make more informed decisions in their work for the organization.

■ Planning for easy changes in the future. Managing organizational

initiatives systematically preserves the overall quality of the outcomes

for stakeholders and the organization as a whole.

As an analogy, consider a person building a house with only a general

plan and no architectural drawings. By means of routine decisions, myriad

minor compromises occur without any overall intent to compromise:

The number and placement of electrical outlets can affect the use of appliances

and limit future work capacity; unplanned placement of vents and

piping can affect future comfort and ability to manage temperature; and

placement of load-bearing walls can affect remodeling or later modification.

Use of different standards for different parts of the construction can

prevent later consolidation of separate systems.Seemingly minor compromises can erode the overall quality of life for

the occupants and limit what can be done with the house in the future.

Many such ad hoc houses are in fact demolished and replaced because it is

FIGURE 1-2 Benefits of managing organizational initiatives systematically. When initiatives are planned systematically, the results are more effective and efficient, and the organization benefits from the professional development of the project team.

cheaper to rebuild than to remodel, particularly if new standards must be taken into account.

Similarly, taking a more comprehensive view of an initiative—and systematically planning its development, deployment, and resourcing—can provide benefits to the organization as a whole by leveraging its common potential and protecting quality.

Why Organizations and Teams Undertake Projects

Why Organizations and Teams Undertake Projects

People embrace change when the value to be gained makes the pain worth

risking. Thus a project is formed. The assumption is that if a project is

formed, the value of the results will be achieved, and the pain everyone goes

through will be worth the effort. Implicit in project management is the concept

of commitment to change and the delivery of results. It is not always a

good assumption that the people on the project team favor the change or

even support it. They receive it as “duties as assigned” in their job description.

The project manager takes on the role of leader and shapes the commitment

and motivation of the individual team members. If the assumptions

made about the project and its ability to deliver are not realistic and achievable,

it is the project manager’s responsibility to validate or change those

assumptions before embarking on the project. Part of the value set of a professional

is not to take on work that is beyond one’s means to deliver. Sales

and management sometimes “sell” a concept because of its appeal, without

a full understanding of the challenges involved in achieving those results.

After all, nothing is impossible to those who do not have to do it.

If you happen to be the individual selected to implement change, it

feels a lot better if the change is desirable and people support the effort. But

having support at the beginning of a project does not guarantee acceptance

later, when the discomfort of change sets in. And popular support seldom

delivers the value of change over time. If change were that easy, someone

already would have done it. People usually support the comfort and familiarity

of the “old way” of doing things before the project came along. In

some cases the project changes things that people rely on, alters their familiar

data, or replaces their old product or service with a new one. Engaging

and managing the risk of human attachments to their familiar methods is

one task of the project management professional. It takes conscious, dedicated

effort on the part of the project’s sponsors, project managers, and

project teams to deliver change that meets expectations. Increasing the

chances of a successful outcome is one element that gets the team working

together on project management activities, methods, and practices.

Delivering on the project’s commitment to results that have value in a challenging

modern context is what gets people inside and outside the project

to work together toward success.

People embrace change when the value to be gained makes the pain worth

risking. Thus a project is formed. The assumption is that if a project is

formed, the value of the results will be achieved, and the pain everyone goes

through will be worth the effort. Implicit in project management is the concept

of commitment to change and the delivery of results. It is not always a

good assumption that the people on the project team favor the change or

even support it. They receive it as “duties as assigned” in their job description.

The project manager takes on the role of leader and shapes the commitment

and motivation of the individual team members. If the assumptions

made about the project and its ability to deliver are not realistic and achievable,

it is the project manager’s responsibility to validate or change those

assumptions before embarking on the project. Part of the value set of a professional

is not to take on work that is beyond one’s means to deliver. Sales

and management sometimes “sell” a concept because of its appeal, without

a full understanding of the challenges involved in achieving those results.

After all, nothing is impossible to those who do not have to do it.

If you happen to be the individual selected to implement change, it

feels a lot better if the change is desirable and people support the effort. But

having support at the beginning of a project does not guarantee acceptance

later, when the discomfort of change sets in. And popular support seldom

delivers the value of change over time. If change were that easy, someone

already would have done it. People usually support the comfort and familiarity

of the “old way” of doing things before the project came along. In

some cases the project changes things that people rely on, alters their familiar

data, or replaces their old product or service with a new one. Engaging

and managing the risk of human attachments to their familiar methods is

one task of the project management professional. It takes conscious, dedicated

effort on the part of the project’s sponsors, project managers, and

project teams to deliver change that meets expectations. Increasing the

chances of a successful outcome is one element that gets the team working

together on project management activities, methods, and practices.

Delivering on the project’s commitment to results that have value in a challenging

modern context is what gets people inside and outside the project

to work together toward success.

Friday, June 14, 2013

THE RELATIONSHIP OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT TO IMPLEMENTING DESIRED CHANGE

THE RELATIONSHIP OF PROJECT

MANAGEMENT TO IMPLEMENTING

DESIRED CHANGE

Traditionally, project management has been how organizations managed

anything new. Organizations always have used projects to manage initiatives

that found “normal operations” inadequate for the task. Normal operations

are designed to accomplish a certain function, but they lack

flexibility. Managing a project to implement any truly new venture is

fraught with ambiguities, risks, unknowns, and uncertainties associated

with new activity.

Change is often a by-product of projects. Creating a project that operates

differently simply adds to the chaos. “Why don’t we just do it the old

way?” people ask. They usually are referring to the tried-and-true methods

of operations that had the benefit of continuous improvement; for example,

the inconsistencies had already been worked out of them by repetition.

When change is needed, in most cases someone already tried getting the

desired change using operations processes, and the “old way” failed to produce

results. Given the discomfort of change, there is usually a compelling

business reason for organizations and their management to undertake it voluntarily.

Usually, the reason is that change is a necessity. In most cases,

someone in a leadership role has determined that the results of the project

(the product or service and even the change) are desirable and that the outcomes

of making that change have value. In other cases, the dangers inherent

in not creating a project and making the change simply are too risky to

tolerate.

Once the outcome of a project has been established as beneficial, and

the organization is willing to undertake a project, the project manager and

team are engaged. Seldom is the project manager brought in at the earliest

concept development stages, although early involvement of the project

manager occurs most frequently in organizations where projects are linked

to the main line of business. The people who are engaged in the project—

as project manager or team member—are not involved voluntarily in creating

change. “My boss told me to,” is a more common reason why someone

becomes involved in a project.

MANAGEMENT TO IMPLEMENTING

DESIRED CHANGE

Traditionally, project management has been how organizations managed

anything new. Organizations always have used projects to manage initiatives

that found “normal operations” inadequate for the task. Normal operations

are designed to accomplish a certain function, but they lack

flexibility. Managing a project to implement any truly new venture is

fraught with ambiguities, risks, unknowns, and uncertainties associated

with new activity.

Change is often a by-product of projects. Creating a project that operates

differently simply adds to the chaos. “Why don’t we just do it the old

way?” people ask. They usually are referring to the tried-and-true methods

of operations that had the benefit of continuous improvement; for example,

the inconsistencies had already been worked out of them by repetition.

When change is needed, in most cases someone already tried getting the

desired change using operations processes, and the “old way” failed to produce

results. Given the discomfort of change, there is usually a compelling

business reason for organizations and their management to undertake it voluntarily.

Usually, the reason is that change is a necessity. In most cases,

someone in a leadership role has determined that the results of the project

(the product or service and even the change) are desirable and that the outcomes

of making that change have value. In other cases, the dangers inherent

in not creating a project and making the change simply are too risky to

tolerate.

Once the outcome of a project has been established as beneficial, and

the organization is willing to undertake a project, the project manager and

team are engaged. Seldom is the project manager brought in at the earliest

concept development stages, although early involvement of the project

manager occurs most frequently in organizations where projects are linked

to the main line of business. The people who are engaged in the project—

as project manager or team member—are not involved voluntarily in creating

change. “My boss told me to,” is a more common reason why someone

becomes involved in a project.

The Occupation of Managing Projects

The Occupation of Managing Projects

The field of project management includes not only project managers but also specialists associated with various functions that may or may not be unique to projects. Those who identify themselves with the occupation of “managing projects” implement projects across many types of settings. They are familiar with the basics in project management and know how projects are run. They may take on different roles within a project setting or the same role on different types of projects. But they always work on projects. Specialists exist in a type of work associated with projects, such as a project scheduler, a project cost engineer, or a project control special-ist. Others will specialize in the use of a particular software tool, knowing all the features and capabilities of that tool, even targeting a particular industry (see Chapter 12). Some specialists perform a sophisticated proj-ect function, such as an estimator on energy-development sites (a specific setting) or a project recruiter (a specific function). Still others specialize in implementing a unique type of project, such as hotel construction, trans-portation networks, large-scale training programs, or new mainframe soft-ware development.

Some of the individuals associated with projects may have entered the field by happenstance, perhaps through a special assignment or a promo-tion from a technical role in a project. What distinguishes those in the proj-

Project Management 15

ect management occupation from those in the technical occupation of that project is that they choose to tie their future and their development to proj-ect management, expanding their knowledge and skills in areas that support the management of a project rather than the technical aspects of creating, marketing, or developing the product or service resulting from the project. There are thousands of people engaged in the occupation of project man-agement, most of them highly skilled, and many of them extremely knowl-edgeable about what it takes to plan, execute, and control a project.

Emphasis on the Profession of

Project Management

A growing number of people recognize the emerging profession of project management. The profession encompasses not only project managers but also other project-related specialists taking a professional approach to the development, planning, execution, control, and improvement of projects. The profession is getting broader because of a number of factors in busi-ness today:

■ The increased rate of change in the business environment and the economy. It used to be okay to say, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” Today, if you don’t fix it before it breaks, the window of opportu-nity may already be closed.

■ External factors. Technological changes, market changes, com-petitive changes—these all influence projects, as well as chang-ing expectations of those who use or receive the products, services, or benefits of the project. Some may change without the project organization’s participation or knowledge. Government regulations are an example of an external change, as are legal decisions in the courts. Understanding project management is necessary to integrate these changes into the organization’s prod-ucts and services.

■ Internal factors. Some organizations have to release new docu-ments, products, or services to stay in business. Whether it is a software company creating “not so necessary” releases or a govern-ment organization refining aviation maps or making policy changes, the changes may be generated internally. Project managers are need-ed to manage these revenue-generators.

Different industries are driven by varying motives to implement projects:

■ Revenue generation

■ Technology

16 The McGraw-Hill 36-Hour Project Management Course

■ Changes in the environment

■ Changes in markets or competition

The project management profession draws from those in the occupa-tion, but it targets individuals who consciously address the more sophisti-cated and complex parts of project management—building knowledge, skills, and ability over time.

The field of project management includes not only project managers but also specialists associated with various functions that may or may not be unique to projects. Those who identify themselves with the occupation of “managing projects” implement projects across many types of settings. They are familiar with the basics in project management and know how projects are run. They may take on different roles within a project setting or the same role on different types of projects. But they always work on projects. Specialists exist in a type of work associated with projects, such as a project scheduler, a project cost engineer, or a project control special-ist. Others will specialize in the use of a particular software tool, knowing all the features and capabilities of that tool, even targeting a particular industry (see Chapter 12). Some specialists perform a sophisticated proj-ect function, such as an estimator on energy-development sites (a specific setting) or a project recruiter (a specific function). Still others specialize in implementing a unique type of project, such as hotel construction, trans-portation networks, large-scale training programs, or new mainframe soft-ware development.

Some of the individuals associated with projects may have entered the field by happenstance, perhaps through a special assignment or a promo-tion from a technical role in a project. What distinguishes those in the proj-

Project Management 15

ect management occupation from those in the technical occupation of that project is that they choose to tie their future and their development to proj-ect management, expanding their knowledge and skills in areas that support the management of a project rather than the technical aspects of creating, marketing, or developing the product or service resulting from the project. There are thousands of people engaged in the occupation of project man-agement, most of them highly skilled, and many of them extremely knowl-edgeable about what it takes to plan, execute, and control a project.

Emphasis on the Profession of

Project Management

A growing number of people recognize the emerging profession of project management. The profession encompasses not only project managers but also other project-related specialists taking a professional approach to the development, planning, execution, control, and improvement of projects. The profession is getting broader because of a number of factors in busi-ness today:

■ The increased rate of change in the business environment and the economy. It used to be okay to say, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” Today, if you don’t fix it before it breaks, the window of opportu-nity may already be closed.

■ External factors. Technological changes, market changes, com-petitive changes—these all influence projects, as well as chang-ing expectations of those who use or receive the products, services, or benefits of the project. Some may change without the project organization’s participation or knowledge. Government regulations are an example of an external change, as are legal decisions in the courts. Understanding project management is necessary to integrate these changes into the organization’s prod-ucts and services.

■ Internal factors. Some organizations have to release new docu-ments, products, or services to stay in business. Whether it is a software company creating “not so necessary” releases or a govern-ment organization refining aviation maps or making policy changes, the changes may be generated internally. Project managers are need-ed to manage these revenue-generators.

Different industries are driven by varying motives to implement projects:

■ Revenue generation

■ Technology

16 The McGraw-Hill 36-Hour Project Management Course

■ Changes in the environment

■ Changes in markets or competition

The project management profession draws from those in the occupa-tion, but it targets individuals who consciously address the more sophisti-cated and complex parts of project management—building knowledge, skills, and ability over time.

WHY MAKE A DISTINCTION BETWEEN PROJECTS AND OPERATIONS?

WHY MAKE A DISTINCTION BETWEEN PROJECTS AND OPERATIONS?

It is important to make a distinction between projects and operations for several reasons, the first of which is that there are major differences in:

■ The decision-making process

– The delegation of authority to make changes

– The rules and methods for managing risk

■ The role expectations and skill sets

– The value sets

– The expectations of executive management for results

– Reporting relationships and reward systems

Project scope or complexity can vary, so size can cause a project to fall within the generally accepted definition of project. A subgroup enter-prise unit may initiate its own products or services using projects, complete them autonomously with a single person in charge, and then turn them over

12 The McGraw-Hill 36-Hour Project Management Course

to another group to operate. Whether this is a project or not depends on its temporary nature and reassignment of the staff member after completing the unique product or service (contrasted with just moving on to another job assignment).

The Decision-Making Process

The decision-making process relies on delegation of authority to the project manager and team to make changes as needed to respond to project demands. A hierarchy of management is simply not flexible enough to deliver project results on time and on budget. The detailed planning carried out before the project is begun provides structure and logic to what is to come, and trust is fundamental to the process. The project manager uses the skills and judgment of the team to carry out the work of the project, but the decision authority must rest with the project manager. Whether the project is large or small, sim-ple or complex, managed by a temporary assignment of staff from other groups (matrix structure) or with full-time team assignments, the delegation of authority is fundamental to the project manager’s ability to perform the job.

Projects with a strong link to the organization’s strategic objectives are most likely to be defined by executive management and managed at a broader level, with higher degrees of involvement and participation from multiple affected departments. Depending on organizational level, the proj-ect manager’s involvement in establishing strategic linkages for the project with the organization’s mission will be more or less evident. Some larger organizations use a process of objective alignment to ensure that projects complement other efforts and advance top management’s objectives.15 Projects at higher levels in the organization probably will state the link with the organization’s mission in their business case and charter documents. Projects at a lower level will need to clarify that link with management to ensure that they are proceeding appropriately in a way that supports the organization’s mission.

It is unlikely that a project linked directly with the organization’s cur-rent strategic initiatives would be implemented by a single person; a team would be assigned to implement it. The project manager has delegated authority to make decisions, refine or change the project plan, and reallo-cate resources. The team conducts the work of the project. The team reports to the project manager on the project job assignment. In non-“projectized” organizations, team members might have a line manager relationship for reporting as well. Line managers have little authority to change the project in any substantial way; their suggestions are managed by the project man-ager—along with other stakeholders. (Line managers, however, do control promotions and salary of “temporary” project team members.)

A subgroup project generally has more input from local management, less coordination with other departments, and generates less risk for the

Project Management 13

organization should it fail to deliver. It might be coordinated by an individ-ual working with a limited number of other people for a few weeks or months until completion of the deliverable. In many large organizations, only larger projects of a specific minimum duration or budget are formally designated as projects and required to use the organization’s standard proj-ect management process.

Role Expectations and Skill Sets

Whereas a few people can accomplish small projects, larger projects— especially those critical to an organization—tend to be cross-functional. Participation by individuals from several disciplines provides the multiple viewpoints needed to ensure value across groups. An important high-level project will be more likely to involve people representing various groups across multiple organizational functions; it may even be interdisciplinary in nature. The varied input of a cross-functional team tends to mitigate the risk of any one group not supporting the result. Interdisciplinary participation also helps to ensure quality because each team member will view other team members’ work from a different perspective, spotting inconsistencies and omissions early in the process. Regardless of whether the effort is large or small, the authority to manage risk is part of the project manager’s role.

Basic project management knowledge and understanding are required for the individual project manager to complete smaller projects on time and on budget. However, professional-level skill, knowledge, and experience are necessary to execute larger, more complex or strategic projects. The project manager leads, orchestrates, and integrates the work and functions of the project team in implementing the plan. The challenges of managing teams with different values and backgrounds require excellent skills in establishing effective human relations as well as excellent communication skills and team management skills. Honesty and integrity are also critical in managing teams that cross cultural lines.

The project manager of a small project may carry the dual role of managing the project team and performing technical work on the project. The project manager of a large, strategic, complex project will be perform-ing the technical work of project management, but the team will be doing the technical work necessary to deliver the product or service. Often a larg-er project will have a team or technical leader as well and possibly an assis-tant project manager or deputy. Small projects are a natural place for beginning project managers to gain experience. The senior project manag-er will be unlikely to take on small projects because the challenges and the pay are not in line with the senior project manager’s level of experience. An exception, of course, would be a small, critical, strategic project for top management, although if it is very small, it too could be considered simply “duties as assigned.”

14 The McGraw-Hill 36-Hour Project Management Course

People who work in project management will have varying levels of skill and knowledge, but they all will be focused on the delivery of project results. Their background and experience will reflect the functional spe-cialties within their industry group, as well as the size of projects they work on. The diversity of projects is so broad that some people working in the field may not even recognize a kinship or commonality with others in the same field. They may use different vocabularies, exhibit diverse behaviors, and perform very different types of work to different standards of quality and with differing customs and behaviors.

The project management maturity of the organization hosting the project also will cause the organization to place value on different types of skills and experience. A more mature project environment will choose pro-fessional discipline over the ability to manage crises. A less mature organ-ization or a small project may value someone who can do it all, including both technical and management roles, in developing the product and run-ning the project.

It stands to reason, then, that hiring a project manager from a differ-ent setting or different type or size of project may create dissonance when roles, authority, and alignment with organizational strategy are involved.

It is important to make a distinction between projects and operations for several reasons, the first of which is that there are major differences in:

■ The decision-making process

– The delegation of authority to make changes

– The rules and methods for managing risk

■ The role expectations and skill sets

– The value sets

– The expectations of executive management for results

– Reporting relationships and reward systems

Project scope or complexity can vary, so size can cause a project to fall within the generally accepted definition of project. A subgroup enter-prise unit may initiate its own products or services using projects, complete them autonomously with a single person in charge, and then turn them over

12 The McGraw-Hill 36-Hour Project Management Course

to another group to operate. Whether this is a project or not depends on its temporary nature and reassignment of the staff member after completing the unique product or service (contrasted with just moving on to another job assignment).

The Decision-Making Process